A week ago Canada marked the first (official) National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, encouraging all of the people of Canada to reflect on the injustices and lasting impacts of colonialism on the Indigenous Peoples of this land. This day has grown to national recognition from its roots as Orange Shirt Day, intended to memorialize the events and impacts of Canada’s very own genocide. I am not an Indigenous Canadian, and in posting today I do not seek to speak for Indigenous Canadians; there has been far too much of that already. But as a friend, neighbour and ally of the Secwépemc people, I offer my tiny platform to amplify their message.

I would like to begin by acknowledging the persisting and unceded sovereignty of the Secwépemc people to their traditional territory, Secwepemcúl̓ecw. I thank the Secwépemc people, especially the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc for sharing their home with me. I feel infinitely lucky to have been raised here; without this place and this community I would not be the person I am. I am grateful to all Secwépemc for their immense resilience and strength in the face of suffering, tragedy and betrayal. Your unwavering dedication to truth, healing and harmony is truly a shining beacon of hope in this fearful and uncertain world.

I encourage everyone to learn about the Secwépemc in their own words

me7 w7ec-kt wel me7 yews (We Will Always be Here)

In honour of the first National Day for Truth and Reconcilliation Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has premiered this moving video that bears witness to the beauty of Secwepemc people, language, lands, and cultural expression.

“Kukwstsétsemc to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation for helping us bring this project to light.”

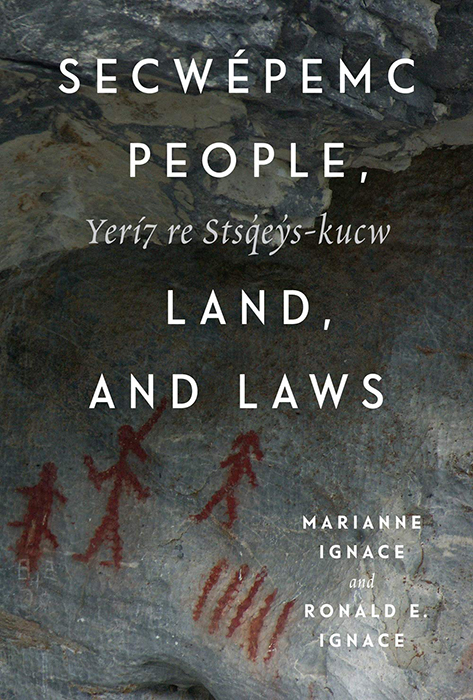

Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws: Yerí7 re Stsq’ey’s-kucw

by Marianne and Ronald Ignace

I cannot recommend this book enough. It is an enthralling and carefully researched masterpiece weaving together the culture, language and ~10,000-year history of the people of the Interior Plateau, while at the same time thoughtfully examining humanity’s “ways of knowing” our past.

I grew up in a place called Kamloops, a dusty unknown city near the far western edge of the former British Empire. From a global perspective my hometown was an unexceptional place in the middle of nowhere, that was until May 27, 2021, when news of 200 unmarked children’s graves were confirmed at the site of the former Kamloops Residential School and the eyes of the world fell upon us. As the world reacted with shock and horror, many locals were not surprised by the announcement. This is not to say our hearts were empty, the outpouring of grief and emotion was immense. It’s just that this finding was not a surprise, it was the worst kept secret in the valley. Brave survivors have always shared their stories; these awful truths were always known, even if only discussed cautiously in hushed tones. Truths that were (and are still) denied both officially by governments and informally by countless individuals. While not the first report of unmarked graves at the sites of Canadian Residential schools, this discovery and the attention that accompanied it served as the spark that ignited a fresh, burning desire for truth and reconciliation among indigenous and non-indigenous peoples alike. Today, in this spirit I seek to tell truth, while illuminating some of the history, culture and unique knowledge of the Secwépemc people that this genocide sought, but failed, to erase.

The systematic genocide of Indigenous Canadians was accompanied by the popular myth that they were “savage” and “uncivilized” people. Through ignorance and hate, policy and propaganda the diverse indigenous people of Canada were overwhelmingly amalgamated in the popular consciousness into a single entity: the “Indian”. A racist and inaccurate term still used in the Canadian Constitution. All as a part of a system of propaganda and control designed to legitimize the sovereignty of the dominion of Canada. A cornerstone of this myth was the observation that Indigenous societies within Canada had no written language; this was used to argue for their intellectual inferiority and against the reliability of their histories. However, this is an argument that doesn’t hold up to scrutiny, neither in light of the history and function of writing, nor in the face of the achievements of the complex “pre-contact” cultures of Canada.

Writing is a system of human communication that represents a natural language (spoken or signed) with symbols (drawn, carved, typed ect). A technological innovation that allows the recording and transmission of ideas, to oneself or others, across both distance and time. At the same time written language is a medium that enhances the human mind’s ability to learn, reflect and recontextualize knowledge. Despite the utility of writing systems, they have only emerged within a handful human societies, those being Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica (plus a few ambiguous cases). From these few instances the knowledge of writing spread, morphing and multiplying into many forms as it was passed between individuals and cultures forwards across hundreds of generations. For writing to develop and persist in a society there must be an inciting factor, some information that is too much for a group to manage reliably from memory alone. Further a convenient and widely available medium to record on is required, such as clay tablets, papyrus, strips of bamboo or paper.

© Claus Ableiter nur hochgeladen aus enWiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While the significance of writing in the context of human history is undeniable, it is not the only method for recording and sharing knowledge. Perhaps my favourite example comes from the Andes, where arrays of knotted cords known as quipus were used for encoding information via combinations of knot style, placement, colour, fibre and ply direction. In a sense the people of the Andes “wrote” in the only suitable medium available to them: wool. Oral traditions were the only method available for transmitting knowledge for the majority of human existence and did not cease after writing was adopted. For most of the history of writing, it was a technology controlled by social elites, limiting most from accessing or contributing to their society’s recorded history. Widespread literacy among the lower classes only became common in the 20th century, and only with the rise of the internet has the writing of average people come to prominence. Written language, like any technology, has limitations and biases; and yet, despite this, near exclusive authority was given in the Old-World civilizations and their colonies to written records above all others. As noted by John Foley in Sighs of Orality: “… oral tradition never was the other we accused it of being; it never was the primitive, preliminary technology of communication we thought it to be. Rather, if the whole truth is told, oral tradition stands out as the single most dominant communicative technology of our species…”. This is not a new observation either: Plato famously criticized the written transmission of knowledge as deficient and shared his most fundamental teachings only orally. Throughout history, various peoples developed strategies to enhance learning and recall, including mnemonic devises and performative traditions which continue to the modern day.

For the Secwépemc their ancient stories (stsptekwll) are said to be “written onto the land”, pairing landmarks and stories that record knowledge of historical events, ecological realities, and the rights of the people as laid down by the people who came before. Rather than development of a written form of their language, the spoken form developed unique and complex features that reinforce the connections between culture, experience and cognition. As the Mariane and Ron Ignace so eloquently put it: “Secwepemctsín speaks to the dynamic relationships among humans, all other living things, the land, and the cosmos, and in doing so it encodes the cultural knowledge that generation of past Secwépemc in turn inherited from their ancestors”. These oral histories are not meant to stand alone, are tied to the context of the telling. They operate on multiple levels, forging connections between concepts and inviting conscious reflection as to their meaning and relevance. In this way places in Secwepemctsín are not named for famous people, and instead are derived from combinations of roots that together describe the shape, features and resources of the place. For example the name Kamloops is an anglicization of the Secwepemctsín name Tk’emlúps, which is built from t the prefix for “on top of”, plus the root kem for “two things coming together at an angle”, plus the suffix l indicating perpetuality, then ups “confluence (also a pointed buttock shape)”. Since this is the place where the North and South Thompson rivers meet this is most often translated as “meeting of the waters”, but as you can see the individual lexical pieces convey a detailed picture of the shape and properties of the land. The Secwépemc oral system of communication and understanding ties the past, present and future together; providing the people with the knowledge to live prosperously on their land.

found in each issue

© Skookum1 at en.wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

That is not to say that the Secwépemc represent a conservative and unadaptable culture, instead they are known for sharing knowledge through cultural exchange and integrating new ideas and technology into their lives. For example metallurgy and horse husbandry were both practiced in Secwepemcúl̓ecw before the arrival of Europeans, learned and traded from their allies. This is also not to imply that the Secwépemc, or any of the Interior Salish peoples, were resistant or hostile to the idea of written language. Father Le Jeune noted the enthusiasm with which the interior peoples learned to read and write Chinook Wawa, the trade language of the day, using Chinook Shorthand. At this time a Nlaka’pamux man by the name of Charlie Mayous quickly adapted the system for writing in Nlaka’pamuxcin, a neighboring language closely related to Secwepemctsín. Travelling with Father Le Jeune he taught at least six Secwépemc to write their own language in shorthand, and within a decade literacy among the Secwépemc was widespread. Between 1892 and 1915, Father Le Juene and his local assistants published the Kamloops Wawa newsletter in Chinook but also Secwepemctsín, written using shorthand and reaching ~1,500 subscribers. The local people recognized the utility of writing as a technology and used their literacy skills to enhance their daily lives by composing letters, posting wanted ads, sharing songs and more. The technology of writing did not replace the Secwepemc oral traditions but served to supplement them.

Of course, in the 1920s when attendance at the Residential Schools became mandatory, both speaking Secwepemctsín and writing in shorthand was heavily punished. The books and newsletters written in Secwepemctsín were hidden away from the children and eventually destroyed. It was not until the 1970s that linguists and local speakers developed the modern version of the Secwépemc alphabet based on the Latin alphabet, such that speakers of Secwepemctsín once again had the tools to read and write in their own language.

12 responses to “On Truth and History in Secwepemcúl̓ecw”

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to construct my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks a lot

LikeLike

Thanks for your question. Apologies for not replying sooner, I am new to blogging and all my comments got caught in the spam filter.

I built this using the wordpress twenty-twenty two template. The colours I chose myself; my aunty is an artist, and I like to think I got my colour sense from her!

LikeLike

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may come back yet again since I bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide other people.

LikeLike

Great article! There’s so much history that doesn’t get shared or taught in school – we need more writers like you!

LikeLike

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to this brilliant blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group. Talk soon!

LikeLike

Thanks, that is very flattering! I am just starting out, but perhaps I will add a donate button in the future.

LikeLike

I was very happy to discover this page. I need to to thank you for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely appreciated every bit of it and i also have you saved to fav to check out new things in your blog.

LikeLike

Awe thanks!

LikeLike

hey there solid blog website and layout. I am hoping I am not annoying you I merely wanted to inquire precisely what wordpress plugin you use to show the newest commentary on your blog? I want to do exactly the same for my free apple iphone page but I cant find the plugin or widget for it. Thanks for your time

LikeLike

I don’t use any plug ins, just the stuff built in to my theme.

LikeLike

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So good to seek out somebody with some unique ideas on this subject. realy thanks for beginning this up. this web site is one thing that is needed on the web, somebody with a little originality. useful job for bringing something new to the internet!

LikeLike

Can I simply just say what a comfort to discover someone that truly knows what they’re talking

about on the web. You definitely realize how to bring a problem

to light and make it important. A lot more people ought to look at this and understand this

side of the story. I was surprised that you are not more popular given that you surely possess the gift.

LikeLike