There is a place in Cascadia, in the south of Secwepemcúl̓ecw, where nature performs a wondrous act of transformation. Since the 1860’s this place has been known as “Adams River” in English, after the baptismal name of the local Chief Sel-howt-ken. After over a century of resource exploitation by colonists, in 1989 the lower Adams River watershed was protected by the establishment of Rodrick Haig-Brown Provincial Park. Initially named after the renowned conservationist, the park was renamed in 2018 to reflect the traditional name used by local people for millennia.

The old-and-new name is Tsútswecw, pronounced like ‘choo-chwek’, meaning roughly “many creeks/rivers converging”.

Like most Secwepemctsín place names, it captures the features and essence of the landscape: this is a dynamic meandering waterway, braiding around islets as it is fed by numerous, often seasonal, creeks. It is to this place of many names and many creeks, that the salmon return year after year.

Battling immense currents, hungry predators and human barriers, these intrepid fish swim thousands of kilometers from the Pacific Ocean to spawn in the waterway where they themselves were born. At the end of their epic and arduous journey they make a final sacrifice, to give the offspring they will never meet the best chance at life. By building their body mass from food in the ocean only to become food on land, they are in essence a pump: natural machines shifting countless tons of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous etc. from the ocean to the land. In the watersheds of Cascadia, there are five species of salmon that make the trip, each with their own niche: the Chinook, Pink, Chum, Coho and Sockeye.

At Tsútswecw, depending on the year and season all but Chum can be found laying the foundation for the next generation. It is the crimson skinned Sockeye that are the stars here though, even in the leanest years of their four-year dominance cycle, they are so numerous that the river appears to run red. Or at least that is how it should be, but it is no secret that the salmon of the Fraser River watershed have been struggling.

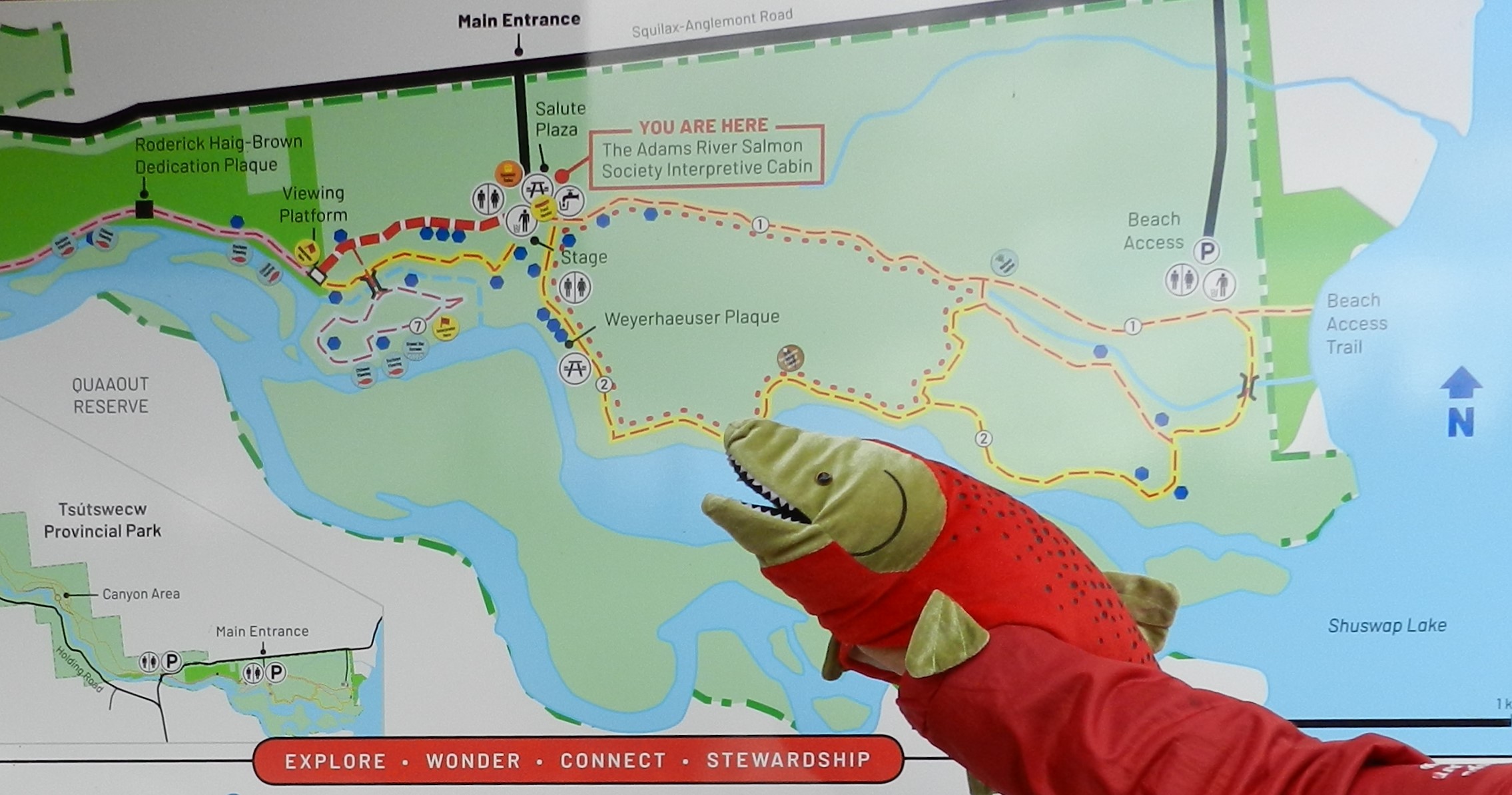

The last time I saw the salmon run at Tsútswecw was in 1998, the last dominant Sockeye run of the 20th century. So last year, on Thanksgiving, my dad and I set out with cameras in hand to take in the spectacle. It was a beautiful clear day, albeit with a chill in the air; the foliage had only just begun to take on its autumn colours. We had chosen the day purposefully, to coincide with the Fall Market; we were eager for an opportunity to enjoy the company of our community, as opportunities for this have been limited by COVID, fire smoke and other climate crisis related events. After our fill of browsing stalls, buying local art, and sampling jams we headed to the interpretive cabin where volunteers share the magic and science of the salmon with guests. A volunteer and her handy puppet directed us to the most active spawning sites.

As we ventured along the trails, deeper into the park, the fragrance of the forest swelled, inundating our senses with the gentle aroma of pine, fir, hemlock, and cedar. From my last visit, I expected the smell of the decomposing salmon to be overwhelming, but as we approached the river it was barely noticeable. Perhaps because our sense of smell fades somewhat as we age, or simply because my last visit was during a dominant run.

From the Plaque Channel Trail we could spot large Chinooks and a few Sockeye through the gaps in the vegetation. The bank here is steep, but in places the roots of the cottonwood trees form natural stairs, inviting us down to the water level. Dad took the first try with the waterproof action camera, spying on the majestic Chinooks. Despite to the seemingly calm surface, the current was strong and keeping the camera stable was challenging.

Chinook salmon, also known as Tyee or King, are the largest of the pacific salmon, and in general their reproductive success is highly correlated with body weight. The females reach maturity at three years, but generally stay at sea for three to five years (and as many as eight!), before returning to their home stream to lay eggs.

The males come in two varieties. The hooknose males mature alongside their female counterparts, and are of similar size. During their return journey their bodies metamorphasize into their sexually mature form, their jaws developing into their characteristic hooked kype. These large males are the preferred spawning partners of the females. Jacks, in contrast, are small (>60 cm) males that return after only a year or two. While they do reach reproductive maturity as they return, they don’t develop like their fully mature brothers. They are also known as “sneak” males, as their strategy is to dart in and “contribute” as another pair is spawning. These precocious young males aren’t cheating the system though; they actually provide a guarantee of gene flow between birth cohorts, keeping the population healthier overall. Both genetic and environmental factors influence the ultimate fate of any given male.

After an hour or so with the Chinooks, we made our way to the Island Loop Trail to visit the Sockeye. The viewing platform, the visitor area, the trails have all changed, even the course and configuration of the river channels themselves shift over time. And yet for me this was the most nostalgic part of our visit. As I stepped through the shady underbrush and onto the rocky beach, I was overwhelmed by brilliant light reflecting off the sun bleach stones. My ears filled with the rush of flowing water and the din of the gathered crowd. Children, equal parts fascinated and grossed-out, were investigating rotting fish with poking sticks. It felt for a moment like I has been transported back to that first time I came here, a little girl overwhelmed by the majesty of nature.

Wherever the river shallows the bodies of spent spawners accumulate, in various stages of decomposition. By dying, the parents give the nutrients and energy from their own bodies to the ecosystem that their children will grow up in. Feeding them indirectly by fertilizing a garden of microscopic organisms. Like a giant pulse, free energy and rare nutrients from the ocean make their way through the food web. The salmon that don’t make the full journey also contribute to this pulse, distributing their atoms and calories through predators or scavengers along the way. Thus, the salmon connect the sea and the land in a very real sense.

At the island loop most of the spawners were Sockeye. Their name is an anglicization of suk-kegh, meaning “red fish” in the Halq’eméylem language of the Salish Sea. In their ocean form the Sockeye are silver, only developing their characteristic red bodies and green faces during their return migration. The males also develop a kype like their Chinook cousins. The Sockeye have a four year life cycle, with a few individuals (male or female) returning a year earlier or later than their birth cohort. You might expect roughly the same number of fish to return annually, but the Sockeye disagree; many of these populations have a dominant line. This means that bulk of the population, the dominant line, spawns in year 1 of the cycle; year 2 is known as subdominant and has ten times fewer spawners; while years 3 and 4 are known as weak lines, representing a further ten times reduction in returning fish. The source of the dominance pattern is somewhat mysterious. It can be disturbed by catastrophic events like landslides, over fishing, and heatwaves; reestablishing itself over time, but often shifting the dominant line to a new year.

The dominant line of the Adams River Sockeye are set to return this year, and it is still unclear what to expect. After a century of decline the 2010 run was the largest on record, shocking everyone. In contrast, their children and grandchildren, the 2014 and 2018 runs respectively, failed to repeat their success. Will the great-grandchildren of this legendary run be a boon for their species, or will they fall victim to the same forces as their parents?

Only time will tell.

One response to “Where the Water Runs Red with Life”

Great article! I didn’t know that there are cycles to the strength and numbers of the generations of spawn we observe each year! Great video footage too!

LikeLike