What are we and where do we come from?

The human animal is perhaps best differentiated from the other fauna by the effort we put into understanding ourselves. From this sustained and collaborative cultural effort, we have come to glimpse deep truths of our enigmatic animal selves. Although the life-histories and lifeways of our individual ancestors are shrouded from us by the cloak of time, we are still lucky in a way; we have come to understand that the forces of destruction are inefficient and random. Pieces of the past persist until destroyed, hidden all around us in many forms: not only as fossils buried in the Earth, but also recorded as isotopic ratios, stored within the molecular machinery of our cells and so on. No single record of the past preserves the whole truth; it is only by considering evidence together that we can constrain the possibilities and bring the past into focus. It is in that spirit that I share my version of the story of human origins. You will find no magic in my telling; the only forces at work emerge from the infinite interconnected complexity of the natural universe in which we find ourselves. There can be no doubt that in many ways we stand apart from the other organisms, capable of so many amazing things. But make no mistake, we are still creatures created by the natural forces of the universe, just like everything around us. And so, before we explore more recent events please enjoy this detour to our deepest past (about 20 to 10 million years ago), from a time before our ancestors were yet human.

Our ancient ape ancestors, like theirs before them, spread and diversified throughout the lush forests of their world. Their world is our world, just some twenty million years in the past; a warm and wet Earth relative to our own. As the slow collision of continents permitted, they dispersed in waves from Africa into Eurasia. For these ancestors there were no borders between places, only between landscapes that could and could not support them. No concept of species, only potential mates. The scale of the Earth was beyond their capacity of comprehension; each individual blind to their place in the inter-braiding streams of relatives we call “primate evolution”. For millions of years they went about their lives, raising their families to forage in the sprawling forests of Afroeurasia. With clever minds and trichromatic colour vision, they sustained themselves and their children on fruit, seeds, and other herbivory; shrewdly supplementing their diets with insects, small animals, and whatever tasty morsels they found.

Every ape is born into this world helpless; a high stakes gamble thrust upon us by the generation prior. We have the potential to develop strong dexterous bodies and complex adaptable brains, but in exchange we must survive our long childhood and adolescence. In a sense every one of us is our genome, the inborn chemical schematic of what we could be. But this biochemical code directing our cells has flexibility built in, buffering us against all manner of nature’s variables. Our animal self is thus created at the confluence of chemistry and the countless influences of the world around us. To grow to our full potential size, we must be well fed. To make a complex and healthy brain, we need nourishment and experiences to shape the developing structure. Our long trek to adulthood provides us time to build and refine our neurocircuitry around not only our childhood experiences, but things that we experience with our adult shaped bodies. We are among the best of nature’s learning machines. And yet all of this on our own is impossible; it is only with the care of our community that we may grow into adults. Many essential instructions for our survival are thus encoded not in the DNA of our genomes, but in the minds of our community, trading the security of genetic hard coding for the capacity known as “culture”. A wager made unconsciously and over uncountable generations by our ancestors; worthwhile only if the environment was favourable. For the closed canopy forests they preferred, the early Miocene conditions were favourable indeed.

The fossil record, though fragmentary, attests populations of apes across the Afroeurasian landmass. Though, the number of species and exact relationships between them is impossible for us to know with high confidence. Certainly, there were boundaries between populations in many forms: physical like mountains, rivers, deserts, or seas; biological such as reproductive incompatibility, transmissible disease, or dietary specialization; and perhaps even cultural factors including mate choice, or lifestyle. But these boundaries are flexible, shaped and reshaped by the world and the inevitable passage of time. The concept of a species itself is problematic. In truth “species” is a word we invented to describe boundaries we observe in nature, and nature is too busy and ancient to be swayed by the categories we imagine for it. Take the case of our smallest ape cousins: the family Hylobatidae, those clever, agile, and arboreal mavericks of the Southeast Asian jungles. If we counted their species based on anatomy, dentition, colour, vocalizations, diet, homeland, or any combination of these obvious characteristics we could arrive at a number, about 20 or so, but with so many edge cases and uncertainties to render the categories dubious. Both in the wild and in captivity (and to the dismay of some taxonomists) breeding pairs of Gibbons can form between individuals of “different species” and can yield fertile offspring. A puzzling observation on its surface. Fortunately, our modern toolkit contains sophisticated methods to study the complex molecular workings of living things; from their methodical application we have learned that the lines between species are blurry.

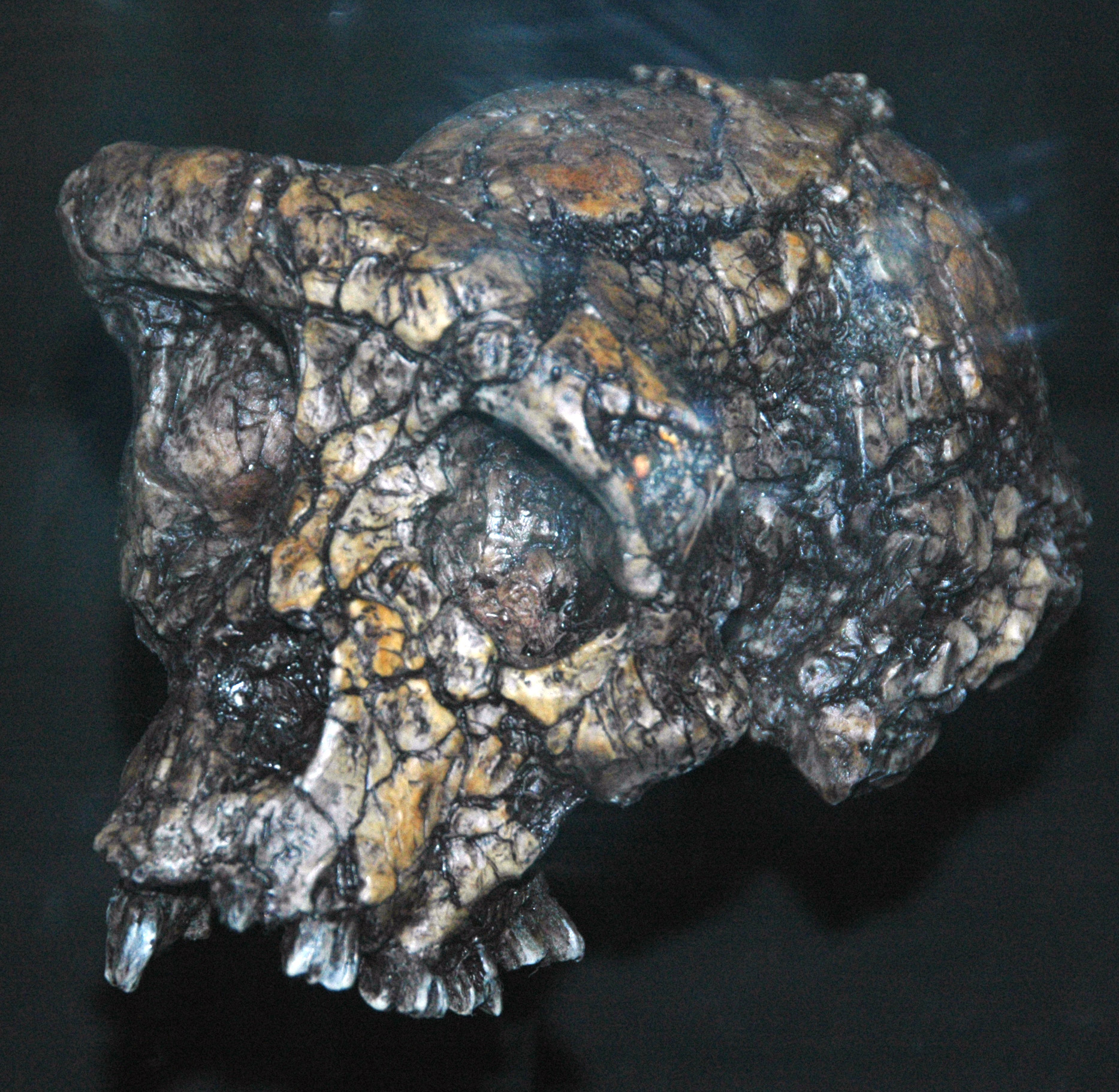

Clément Bucco-Lechat, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sexually reproducing organisms, like apes, develop from the fusion of parental gametes, where each gamete carries one copy of each functionally unique chromosome possessed by that parent (23 per gamete in humans). These two half-genomes work together to develop from zygote, to embryo, to infant, and so on, for as long as they can (you’re doing it right now!). If their genetic instructions are too similar, they might share defects; but if too divergent, their biochemistry can’t cooperate efficiently. Both cases often resulting in unhealthy or nonviable progeny. If they synergize well, and with a bit of luck, the organism will grow into an adult. It is at this stage that nature administers a final test: producing the next generation of gametes. A failure point for many hybrids that are otherwise healthy animals, like mules, where mismatched chromosomes prevent successful meiosis, or result in gametes with incomplete genomes. Thus, the species identity of the parent organisms doesn’t matter, only the compatibility of their genomes.

Genomic technology has confirmed that Gibbons interbreed where the ranges of divergent populations meet, and further has revealed traces of numerous ancient hybridization events. Like other residents of the Sundalands their ancestors were at the mercy of the glacial-interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene. As rising seas chewed peninsulas into archipelagos, populations were isolated for tens or hundreds of millennia. When the waters receded and their forest homes recolonized the exposed continental shelf, the ancestral gibbons could once again intermingle. Traces of these ancient matings are preserved in the genomes of their descendants.

While the gibbon ancestors remained small, our ancestors walked a somewhat different path. Natural selection continued offloading computational and storage tasks from their genomes to their social group’s neurocircuitry. Over generations they grew bigger bodies and brains, made possible by the growing complexity of their shared knowledge. Their childhoods and adolescent periods grew longer as well, to facilitate more time to learn and grow. They became more dependent on their communities as their capacity for social intelligence increased; knowledge and invention compounding on molecular evolution to accelerate adaption. Thus, culture provided yet another implement for the slow hand of evolution to sculpt us. In time our ever-more-clever ancestors developed ways of modifying their environment to their advantage, manipulating materials they found for foraging and protection. Their methods and teachings undoubtably form the foundations of the tool traditions of all their modern descendants, including our own. As their combination of traits proved successful, they too spread from Africa establishing populations across Eurasia.

And yet, the only constant in the universe is change. This was as true for our ancestors as it for us. The warm and humid conditions supporting the pan-Afroeurasian forests could not last forever. And so, they didn’t. Tiny tectonic and astronomical coincidences conspired on a global scale, setting in motion a positive feedback loop that would cool and dry Earth’s climate. Imperceptibly at first rainfall was diminishing, eventually stretching into prolonged droughts. Some ancient rainforests were stressed beyond their limit. The raw energy of the sun penetrated through to the forest floor as the large trees of the canopy died off, their monopoly on photosynthesis dying with them. For grasses and scrub, this was the opportunity they hadn’t known they were waiting for. Powered by the sun’s radiant grace, the resilient underdogs of the plant kingdom spread and evolved. Their proliferation brought fire, which further accelerated the demise of many rainforests. For some forms of animal the shifting climate was an opportunity; their populations swelled and diversified. The grazing herbivores especially grew in both number and body size over generations; their destructive feeding behaviours further pushing out the more delicate closed-canopy ecosystems. This was the rise of the woodlands: new mosaic habitats where hardy trees are spaced apart by grass and shrubs. There were some animals that could not survive the transition, retreating with the forests or going extinct altogether.

What became of our ancestors during this ancient apocalypse? The anti-climactic truth is that they wouldn’t have even noticed. On the scale of a lifetime, at best only fifty years for apes in the wild, the shrinking of the forests would have appeared negligible. Even for a dramatic change, like an earthquake altering the course of a river, without language there was no way to keep alive the memory of such an event. And so our ancestors lived their lives wherever they found themselves, oblivious to the slow fragmentation of their habitat and unaware of an emerging East-West schism as grasslands took over western Asia. The eastern branch flourished in Asia, becoming the Pongins (including the modern Orangutan). They were not alone though, our own Hominin branch continued on in Africa and Europe.

In Antarctica, and on the tops of mountains the world over, greedy glaciers were gulping up moisture. Untiring tectonic forces carved up the ancient Partethys Sea, the north-easternly twin of the Mediterranean, decimating another source of precipitation for the Northern Hemisphere. Flora and fauna adapted to the new arid paradigm spread from Asia into Europe and Africa, mixing with, and replacing local species. Diffusion of ape populations between Africa and Europe continued opportunistically, whenever North Africa/Arabia/the Levant were experiencing a humid period. Gene pools mixing and splitting like the channels of a braided river.

And still, the shifting climate was not done reshaping the apes, but that is a story for another time.

Next time we look inward, to discover the molecular workings of living things and connect the dots between the microscopic world and our everyday experiences.