Cascadia was shaped by glaciation, evidence of this icy past is written into the landscape all around us as expansive coastal fjords, massive deposits of glacial till on the interior plateaus, and deep valleys carved by meltwater, to name only a few. The most recent ice age, the Pleistocene Glaciation, began around 2.58 million years ago, cycling between glacial and interglacial periods in step with the shifting conditions of the Earth climate system. Each new glaciation remodelled the products of the last. During a glacial period, the Cordilleran ice sheet covered all of what is now British Columbia as well as parts of the Yukon, Alaska, Washington, Iowa, and Montana; slowly pouring over the Rocky Mountains in the east to meet the titanic Laurentide ice sheet. This frigid wasteland stretched from the Rockies to the Pacific; conventional wisdom says this rendered the entire Northwest of North America uninhabitable for millennia. As glaciers grew they were pulled by gravity, flowing into the valleys, pushing the plants and animals out. Once continuous populations became divided, severing gene flow and starting the clock on speciation through random genetic drift. Still other forms of life were driven to extinction, never to be seen again. When glaciers receded life began recolonization of the newly ice free habitats, migrating south from Beringia and North from the Americas. And so, the history of Cascadia is written not only in its lands and waters but also in its biology.

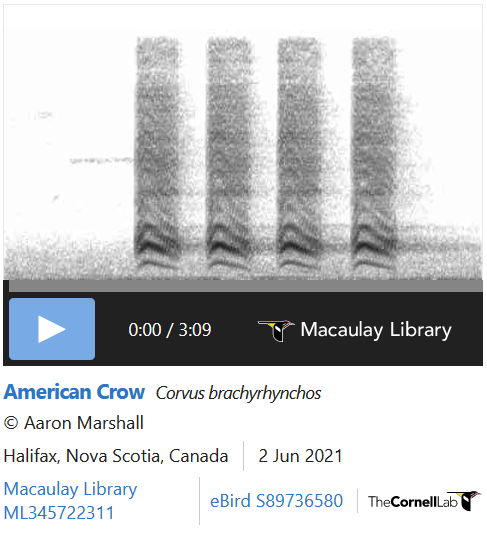

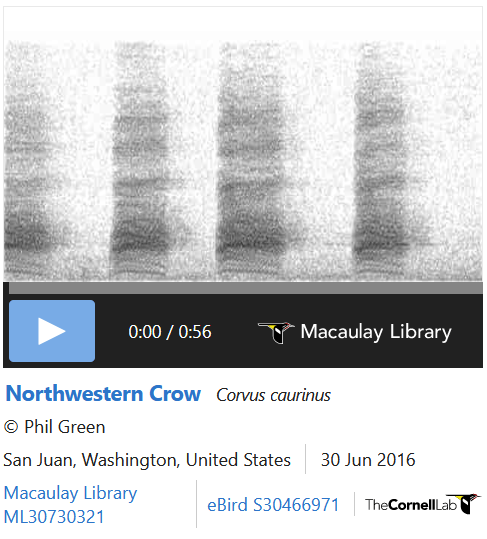

It has long been noted that the crows of the Pacific Northwest are somewhat different than their cousins to the east and south. These Northwestern Crows (Corvus caurinus) on average have smaller bodies and beaks than the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), and their diets are more focused on coastal resources. Perhaps the most apparent difference is between their vocalizations. The call of the Northwestern Crow is ‘squawky’ and even pitched relative the American crow, whose call is clearer and with a rise and fall in pitch. This is what I noticed moving from the interior of B.C. to the coast, which first turned me onto this interesting little mystery. Colonial naturalists in the 19th century designated the Northwestern Crow its own species, but the debate continued. Avian enthusiasts found these two species practically impossible to reliably distinguish in the field. Populations of these species appeared to coexist in around the Salish Sea; individual crows were even noted making both Northwestern and American vocalizations. If you are a birder who has felt mocked by these highly intelligent and cheeky corvids, you are certainly not alone.

As our scientific understanding of the natural world grew, the mystery of the crows of the Pacific Northwest deepened. How did the Salish Sea come to host two varieties of crow? Could these two varieties hybridize, or was there some unseen biological or behavioural barrier? If these were discrete species then glaciation was an obvious suspect in their speciation, but where could that have happened? During glacial periods the southern portion of their modern range was never enclosed by glaciers, while their Northern range was buried under ice. After at least 160 years debating the question, in 2020 a genetic survey of crows was published. This collaboration between the University of Washington and the Burke Museum, included over 250 individuals from across North America, including historic museum samples.

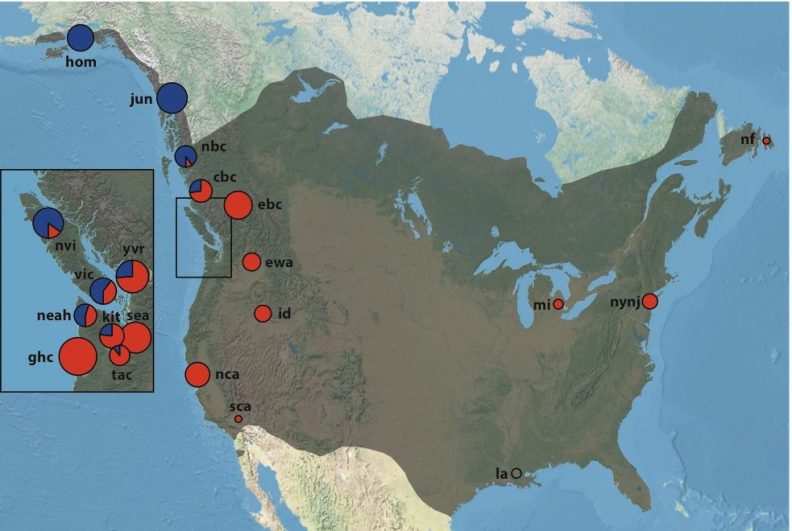

(From Slager et. al., 2020) © 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Their data is clear: Northwestern and American Crows readily interbreed and should be considered a single species; appropriately the American Ornithological Society now recognizes the Northwestern Crow as Corvus brachyrhynchos caurinus, a subspecies of the American Crow.

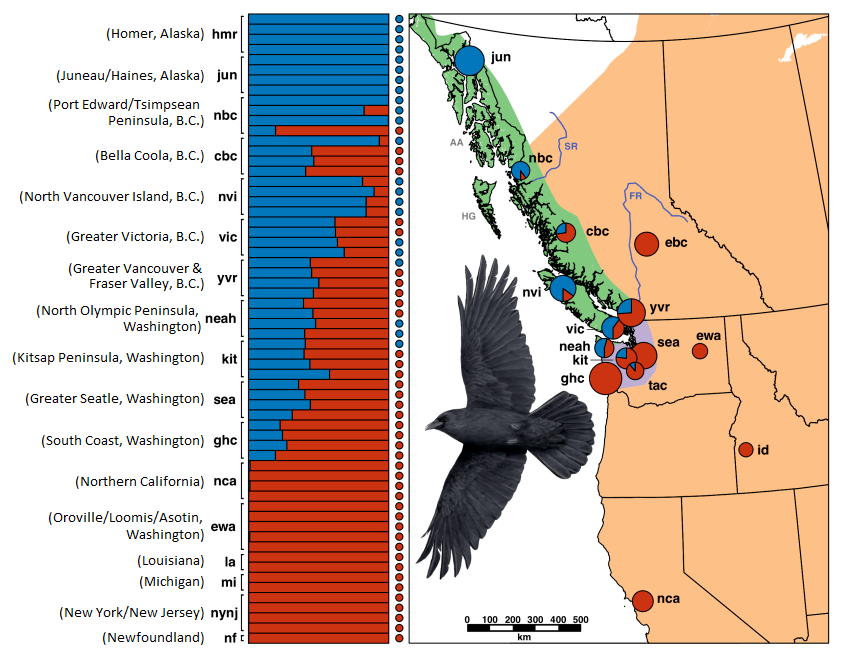

That is not to say that these sister lineages have identical evolutionary histories. The researchers found two mitochondrial DNA lineages among these birds, one they called the American Crow haplogroup (red in their figures) associated with the crows east of the Coast/Cascade mountains and south of the Salish Sea, and another they termed the Northwestern Crow haplogroup (blue in their figures) found exclusively west of the Coast/Cascade ranges and north along the Alaskan coast. They estimate these populations were separated roughly 443,000 years ago, likely during a glacial period; these lineages only came back into contact relatively recently, during this current interglacial period. Both haplogroups co-occur in a hybrid zone, stretching from the north of the Haida Gwaii to the southern extent of the Salish Sea. Nuclear genome sequences reveal extensive admixture between the two lineages in this zone. Perhaps most interestingly, the range of the northwestern haplogroup and the hybrid zone were found to be further north than expected. The implication being that the Northwestern crows lived isolated from their kin along the Pacific coast of B.C. and Alaska, an area once thought to be under ice and uninhabitable, not south of the Cordilleran ice sheet in modern Washington state as some once suggested.

(From Slager et. al., 2020) © 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

This study is just one of many in a growing collection that indicate that ice coverage along Cascadia’s Pacific coast during the Pleistocene Glaciation was not complete. After all it is known that quirks of geography can create “glacial refugia”, ice free pockets where life can wait out a long freeze. During a glacial period water is trapped on the continents as ice, lowering global sea levels and exposing the previously submerged lands of continental shelves for habitation, like Beringia or Doggerland. Further, the seasonal outwash of minerals, liberated from solid rock by the action of glaciers, fertilizes ocean life thus creating new food sources for enterprising terrestrial animals to exploit. It seems that the ancestors of Northwestern Crows did just this, hanging on in refugia along Cascadia’s coast, feeding themselves and their young on the bounty of the tides.

“American Crow Macaulay Library ML30730321.” n.d. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/30730321.

“American Crow Macaulay Library ML345722311.” n.d. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/345722311.

Chesser, R Terry, Shawn M Billerman, Kevin J Burns, Carla Cicero, Jon L Dunn, Andrew W Kratter, Irby J Lovette, et al. 2020. “Sixty-First Supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s Check-List of North American Birds.” The Auk 137 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/ukaa030.

Colella, Jocelyn P., Tianying Lan, Sandra L. Talbot, Charlotte Lindqvist, and Joseph A. Cook. 2021. “Whole-Genome Resequencing Reveals Persistence of Forest-Associated Mammals in Late Pleistocene Refugia along North America’s North Pacific Coast.” Journal of Biogeography 48 (5): 1153–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14068.

Darvill, C. M., B. Menounos, B. M. Goehring, O. B. Lian, and M. W. Caffee. 2018. “Retreat of the Western Cordilleran Ice Sheet Margin During the Last Deglaciation.” Geophysical Research Letters 45 (18): 9710–20. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL079419.

National Committee of the Audubon Societies of America, National Association of Audubon Societies for the Protection of Wild Birds and Animals, and National Audubon Society. 1899. Bird Lore. New York City : Macmillan Co. http://archive.org/details/birdlore211919nati.

Slager, David. 2020. “Genomic and Morphological Analysis of an American Crow Hybrid Zone.” Thesis. https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/45445.

Slager, David L., Kevin L. Epperly, Renee R. Ha, Sievert Rohwer, Chris Wood, Caroline Van Hemert, and John Klicka. 2020. “Cryptic and Extensive Hybridization between Ancient Lineages of American Crows.” Molecular Ecology 29 (5): 956–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15377.

One response to “A Secret History of Crows and Ice”

It’s a tale of two crows! Great article, I learned about a bit about fascinating topic i had no idea about!

LikeLike